Images © Matt Jacobsohn

The ballistic testing per UL 752 has eight primary levels with a few (levels nine, 10, and shotgun) additional, less common ones. Each level contains provisions for different firearms and/or number of bullets fired at the glass (Figure 1).

The firearms used are capable of carrying magazines with varying numbers of bullets. In a majority of cases, these firearms hold more than 10 bullets in a magazine. It is important to note the number of shots fired during the UL 752 test is five. The test protocol does call for these bullets to be in a concentrated area based on the level being tested. For example, levels one to three, which are handguns, require three shots within a 100-mm (4-in.) triangle. Levels seven and eight—for assault rifles—need five shots in a 115-mm (4.5-in.) square. In both cases, if a shooter was to shoot more than 10 bullets into a UL 752-compliant product, the bullets would likely penetrate. This is based on a test performed by the author on a UL 752 Level 1 piece of glass with the corresponding firearm, where the fifth bullet penetrated the glass.

Bullet-resistant glass is heavy and thick, weighing anywhere from 4 to 23 kg (8 to 50 lb) per square foot, and ranging from 20 to 100 mm (¾ to 4 in.)

in thickness. Its laminated composition combines various layers of glass and/or plastics. A UL 752, ballistic-resistant product does not spall, meaning material fragmentation does not occur on the safe side of the material after being shot. This protects anyone on the safe side of glass from flying debris. To produce a no-spall, bullet-resistant glass, a plastic layer (typically polycarbonate) is laminated to the interior surface. Although effective, it does have its negatives—as with any exposed plastic, the risks of scratching and aesthetic degradation are greater than a traditional glass surface.

Bullet-resistant glass should always be installed into a bullet-resistant system (door/frame) with a matching rating. Otherwise, as mentioned earlier, the bullet-resistance rating of the opening will be compromised. These systems, particularly doors, can therefore become extremely heavy, weighing more than 227 kg (500 lb) in some cases. Although much of the weight is in the glazing, the door depending on the type, size, and the material to make it bullet resistant, can affect the overall weight. Doors may be aluminum, steel, wood, and fiber-reinforced polyurethane (FRP) with extra material such as kevlar or steel inside the door and frame. The weight of the frame should not matter as long as is it anchored appropriately. If steel is reinforced, the thickness, and therefore, weight of the steel may affect the level of bullet resistance a frame or door achieves.

Forced entry

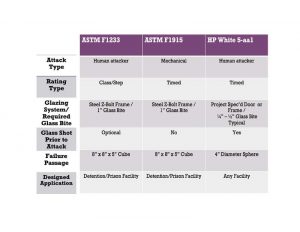

Test methods for forced entry glazing vary greatly, such as:

- not all include ballistics;

- some require the glazing to stop bullets;

- a few use human attackers with implements, while others employ mechanical attack methods; and

- some tests are timed, others are class/step based, while many use the number of impacts and translate these to a timed designation.

In nearly every instance, until recently, these tests methods had one thing in common—they were all tested in similar glazing systems (framing).1

Forced entry glass, or transparent armor can be tested according to the following:

- HP White Laboratories-Test Protocol (HPW-TP) 0500.03, Transparent Materials for Use in Forced Entry or Containment Barriers;

- ASTM F1233, Standard Test Method for Security Glazing Materials and Systems;

- ASTM F1915, Standard Test Method for Glazing for Detention Facilities;

- UL 972;

- 5-aa1, Certification Standards for Retrofitting and Reinforcing of Standard Commercial Entry Systems, Windows and Glazing;

- 5-aa5, Certification Standards for Reinforcing and Testing of Standard FRP and Aluminum Storefront Doors, Frames, Hardware, Glass and Sidelites;

- 5-aa10, Certification Standards for Reinforcing and Testing of Standard Wood and Hollow Metal Doors, Frames, Glass and Hardware; and

- Walker-McGough-Foltz & Lyeria (WMFL) 30 and 60 Minute Retention, Ballistics and Forced Entry Test Procedure (Figure 2).

HPW test method

The following text was the premise for HPW to develop HPW-TP-0100.00, Transparent Materials and Assemblies for Use in Forced Entry or Containment Barriers, the first forced entry transparent armor protocol, in 1983.

Increasing levels of international terrorism and institutional disorder have extended to structures which have, heretofore, generally been free of such assault. The vulnerability of these structures to assault from ill-equipped and untrained attackers is well documented by the success of riots within penal institutions and the illegal occupation of government buildings. Analysis of such incidents indicates that physical barriers suited to the intensity and nature of the attack would have prevented the incident or contained the incident with a limited portion of the structure.

Additionally, “historically these elements have proven to be the most vulnerable portions of the barrier to overt forced entry- or exit-assaults.” The test included ballistics, blunt impacts, sharp tool impacts, thermal stress, and chemical deterioration.