How smart vapor retarders work

A smart vapor retarder reacts to changes in relative humidity (RH) by altering its physical structure. During the winter, when relative humidity is low, it provides high resistance to vapor penetration from the interior. However, when the RH increases to 60 percent or above, its permeance dramatically increases, thus allowing water vapor to pass through, which facilitates the drying of building systems. The moisture building within the wall system is now able to move from the high-moisture concentration area and dry toward the assembly’s interior.

During conditions of low RH, a smart vapor retarder maintains its impermeable state to prevent moisture from migrating and then condensing within the wall system. However, as soon as the material comes into contact with moisture (i.e. 60 percent RH), it opens up and softens its structure to allow the polar water molecules to penetrate through. As a result, the smart vapor retarder pores through which further water molecules can penetrate, and the permeance increases to greater than 10 perms as tested in accordance with ASTM E96’s wet cup method. When the air is humid in the summer, the moisture penetrates through the pores into the building interior, allowing building materials to dry out. If the relative humidity decreases, the pores close up again, and the smart vapor retarder then acts as a barrier to moisture. In the winter, the smart vapor retarder protects the building materials behind it from condensation.

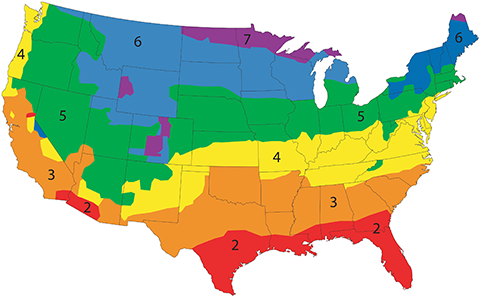

Climate’s role in specifying air barriers

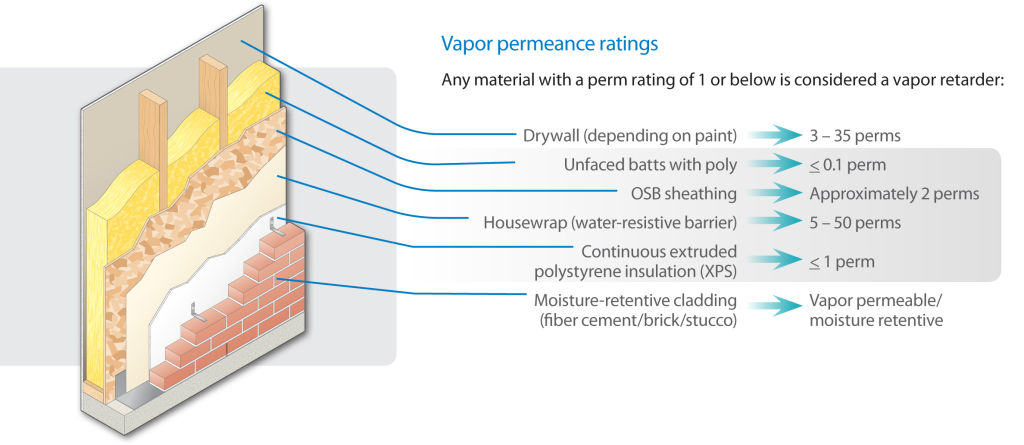

Large portions of North America are considered ‘mixed-climate’ regions, where the moisture drive direction is balanced between winter and summer. In these regions, buildings using traditional polyethylene vapor retarders may successfully keep moisture out of the cavity in the cold season, while essentially trapping it there during summer when the moisture drive reverses. This problem is further exacerbated by the use of moisture-retaining cladding, such as masonry, fiber cement, and stucco, which release moisture into the building cavity.

As such, for cold climates, vapor retarders are required for wall assemblies and should be placed at the wall’s interior side. In heat-dominated climates, the vapor retarder should be placed at the building envelope’s exterior. In most applications, vapor or air barriers should be installed over un-faced insulation before the drywall is installed. Again, smart vapor retarders are a good choice in these mixed-humidity climates because of their ability to adapt to the varying moisture conditions that occur throughout the year.

While smart vapor retarders can reduce the risk of moisture damage in the building envelope by increasing the construction’s tolerance to moisture load, they are not suitable for every climate. Hot climates with high outdoor humidity are always under high RH conditions, which in turn, would cause

a smart vapor retarder to always be permeable and never provide the wall cavity with vapor retarding benefits. These materials also do not work well in buildings with exceptionally high, constant indoor humidity levels, such as indoor pools and spas. However, in rooms with short peaks of high humidity like restrooms and kitchens, the performance of the smart vapor retarder would not be affected because of the buffering action of interior finishes.

Conclusion

A holistic approach to building design is the best way to address moisture and air flow. As architects and builders affect one area like thermal performance, the flow of air and moisture are also impacted. Moisture in the wall is unavoidable, so it is important assemblies are designed with the potential to dry. By incorporating adaptable solutions like smart vapor retarders, occupant comfort can be managed and buildings set up for long-term structural success.

Ted Winslow is product manager, building science, systems, and technical marketing for CertainTeed Insulation. He serves the company as a technical resource on topics ranging from code reviews to sustainability programs and oversees development of CertainTeed insulation systems. Winslow holds a bachelor’s of science degree in mechanical engineering from Temple University. He can be reached at ted.winslow@saint-gobain.com.