Using vapor retarders to manage airflow and reduce moisture

by Katie Daniel | May 6, 2015 2:56 pm

[1]

[1]by Ted Winslow

Industry codes are tightening the building envelope and increasing the required R-value of walls. This is a good thing for energy savings and thermal comfort. Yet, one change to a building’s system sets forth a series of other changes.

The tight-envelope construction techniques to which architects and builders are now required to adhere have led to a steep reduction in air movement through walls. This means moisture gets trapped inside wall cavities without sufficient means for it to escape, leading to reduced drying potential for a wall’s interior. Therefore, the airtight standards for energy efficiency have created new challenges for moisture management that cannot be neglected. This ‘moisture sandwich’ is occurring with increasing frequency as architects design walls and incorporate newer insulation practices to enhance energy efficiency.

How moisture enters a building envelope

The first step is to understand how moisture penetrates wall assemblies. Generally, there are four forces driving moisture through the building envelope:

- gravity;

- capillary suction;

- water vapor diffusion; and

- airborne movement of water vapor.

Gravity moves rainwater down a building’s exterior surface. When there are openings in exterior wall assemblies, such as downward-sloped openings, water will pass through them. This force is typically countered by roof systems designed with shingles and flashings. Also, overlapping, sealing, or covering exterior wall joints in a manner that diverts rain from the building helps keep gravity-drawn water out of the wall.

Another mechanism of water penetration is capillary suction, which is a result of the surface tension of water. Water is drawn inside through tiny pores in building materials, often so small they are invisible to the eye. To hinder this moisture flow mechanism, it is best to break the continuity of materials from the exterior through to the interior to obstruct moisture’s path. Breaks in components can be accomplished by incorporating small cavities that prevent moisture from migrating through all the layers of materials. Specifying moisture-tolerant exterior wall materials like concrete and masonry is also helpful.

A third way moisture enters a building envelope is through water vapor diffusion. Water vapor will pass or diffuse through building materials whenever areas of high and low vapor pressure exist on opposite sides of that material. This movement is from the material’s high vapor pressure side to the low-pressure side.

Water vapor permeance of a building material can be determined through ASTM E96, Standard Test Methods for Water Vapor Transmission of Materials, which measures diffusion using two possible means: the dry cup method (also known as Method A or the desiccant method) and the wet cup method (also referred to as Method B or the water method).1

![airbarriers_BlocksMoisture-ALT-v2-FA_text[1]](http://www.constructionspecifier.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/airbarriers_BlocksMoisture-ALT-v2-FA_text1-e1430936763638.png) [2]

[2]Air movement is yet another way moisture gets inside a building. In fact, air can bring a large amount of moisture into a building if it is not impeded by good construction practices. Compared to moisture entering a building by water vapor diffusion, moisture carried into a building by air can be up to 100 times greater. For example, a 1.2 x 2.4-m (4 x 8-ft) sheet of gypsum board will permit up to 285 ml (9.6 oz) of water to pass through it over a heating season in a cold climate. If, however, a 25-mm (1-in.) hole were to open in that board to permit airflow, airborne moisture flow could add up to 28 L (7.5 gal) of water over the same period. This phenomenon creates an excellent case for making wall assemblies airtight and preventing moisture from condensing on cold surfaces.

Naturally, moisture can enter the cavity from either the inside or outside of the wall—an average family of four can create two to three gallons of water vapor per day from cooking, bathing, and washing dishes and laundry. Over a heating season in colder climates, these moisture loads are driven toward a building’s exterior and penetrate into the wall cavity. Air can transport moisture quantities up to 28 L through holes in the building envelope’s interior side that are as small as 645.16 mm2 (1 si). This has led to an increased focus on developing more airtight wall systems.

While an airtight wall is important, there is need for a means of escape for moisture that gets trapped in the assembly. If there is no established escape plan, then the building has a high likelihood of creating a moisture sandwich inside its walls.

![airbarriers_ReleasesMoisture-ALT-v2-FA_text[1]](http://www.constructionspecifier.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/airbarriers_ReleasesMoisture-ALT-v2-FA_text1-e1430936989614.png) [3]

[3]Making a moisture sandwich

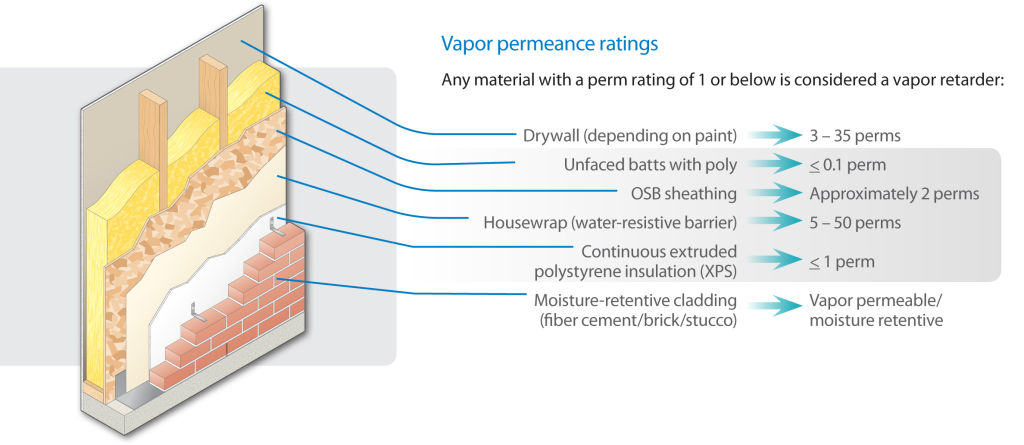

A moisture sandwich occurs when a well-insulated wall system traps moisture from both the interior and exterior components. It is a scenario playing out with frequency as architects design walls and incorporate insulating products that create energy-efficient buildings. For example, many areas of the country are beginning to install exterior insulation to help increase a wall’s R-value, decrease its thermal bridging, and reduce the permeance level.

Extruded polystyrene (XPS) has a permeance level of .03, which is similar to 152.4-µm (6-mil) poly. A common assembly may comprise:

- moisture-retentive cladding like fiber cement, brick, or stucco;

- exterior insulation that acts as a vapor retarder similar to 152.4-µm polyethylene;

- oriented strandboard (OSB), which is semi-permeable at 2.0;

- kraft-faced fiberglass batts at a range of .3 to three or unfaced batts and 152.4µm polyethylene with a permeance rating of .05; and

- dryall with a permeance rating of three to 35, depending on the paint.

Unfortunately, this creates a moisture sandwich: moisture gets into the wall and is trapped between polyisocyanurate (polyiso) foam board on the exterior, and a 152.4-µm polyethylene on the interior with no ability to dry. It is a probable situation that is likely under construction throughout the country at this moment.

Consequences of a moist wall

Having moved beyond the era of leaky buildings, the industry is now facing a new set of challenges stemming from this era of airtight construction. Moisture, when trapped inside a wall cavity for an extended period, can cause building materials like wood, traditional paper-faced gypsum, and steel to eventually deteriorate or corrode. Even R-value goes down when insulation gets moist, and thermal performance is the reason the wall system was constructed to be airtight in the first place.

It is common knowledge moisture buildup can lead to health issues through mold growth that releases potentially harmful spores into the air. These airborne spores can cause occupants to experience acute health and comfort issues that correlate with the time they spend inside the building.

Architects want to design wall systems that are able to dry; otherwise, these types of product deterioration scenarios and mold growth are likely. Since the moisture is within the wall, the issues are unlikely to be found until it is too late. This is when the large and expensive problems like mold remediation and litigation arise.

It is possible to design a continuous airtight wall system that also exerts moisture control.

A great first step is to focus on the management of air and moisture flow through the building envelope. Continuous air barriers and smart vapor retarders are able to address both airflow and manage the moisture profile of the exterior wall cavity. This helps minimize and limit the risk of moisture-based building issues while adding minimal additional labor to projects.

[4]

[4]Changing the drying potential of a wall

Poly vapor retarders are part of the traditional approach to keeping moisture out of a wall, but as mentioned, moisture seems to find its way in, one way or another. Historically, building codes have classified vapor retarders as having a water vapor permeance of 1 perm or less when tested in accordance with the ASTM E96 desiccant/dry cup method. As such, most products are only evaluated under dry conditions. Products like polyethylene film or aluminum foil have low permeance values that remain constant between dry and wet conditions.

Rather than contributing to a healthy wall cavity, vapor retarders can often become part of the problem. These low-perm materials slow the rate of water vapor diffusion, but do not totally prevent its movement. As water vapor moves from a warm interior through construction materials to a cooler surface, the water vapor may condense on these vapor retarders as liquid water that could damage the building. It is for this reason smart vapor retarders are needed. Not only do they retard moisture penetration, but they also increase the potential for materials to dry. The wall’s drying potential must always be greater than the wetting potential so the amount of moisture getting into the system is less than the amount of moisture that can leave it.

Smart vapor retarders, though not required by code, are the better approach to a healthy wall assembly in many regions. Fortunately, building codes are continuing to evolve and adapt; it is important to use progressive solutions that also actively manage conditions within the wall assembly. Design professionals should strive to build beyond current practice—selecting adaptive solutions like smart vapor retarders can be the better practice in various situations.

[5]

[5]How smart vapor retarders work

A smart vapor retarder reacts to changes in relative humidity (RH) by altering its physical structure. During the winter, when relative humidity is low, it provides high resistance to vapor penetration from the interior. However, when the RH increases to 60 percent or above, its permeance dramatically increases, thus allowing water vapor to pass through, which facilitates the drying of building systems. The moisture building within the wall system is now able to move from the high-moisture concentration area and dry toward the assembly’s interior.

During conditions of low RH, a smart vapor retarder maintains its impermeable state to prevent moisture from migrating and then condensing within the wall system. However, as soon as the material comes into contact with moisture (i.e. 60 percent RH), it opens up and softens its structure to allow the polar water molecules to penetrate through. As a result, the smart vapor retarder pores through which further water molecules can penetrate, and the permeance increases to greater than 10 perms as tested in accordance with ASTM E96’s wet cup method. When the air is humid in the summer, the moisture penetrates through the pores into the building interior, allowing building materials to dry out. If the relative humidity decreases, the pores close up again, and the smart vapor retarder then acts as a barrier to moisture. In the winter, the smart vapor retarder protects the building materials behind it from condensation.

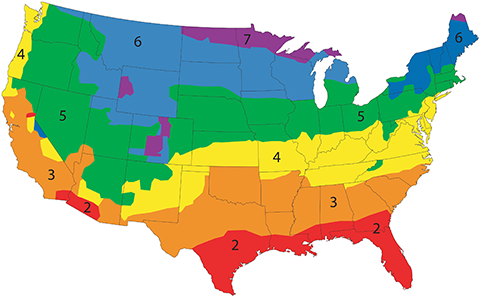

Climate’s role in specifying air barriers

Large portions of North America are considered ‘mixed-climate’ regions, where the moisture drive direction is balanced between winter and summer. In these regions, buildings using traditional polyethylene vapor retarders may successfully keep moisture out of the cavity in the cold season, while essentially trapping it there during summer when the moisture drive reverses. This problem is further exacerbated by the use of moisture-retaining cladding, such as masonry, fiber cement, and stucco, which release moisture into the building cavity.

As such, for cold climates, vapor retarders are required for wall assemblies and should be placed at the wall’s interior side. In heat-dominated climates, the vapor retarder should be placed at the building envelope’s exterior. In most applications, vapor or air barriers should be installed over un-faced insulation before the drywall is installed. Again, smart vapor retarders are a good choice in these mixed-humidity climates because of their ability to adapt to the varying moisture conditions that occur throughout the year.

[6]

[6]While smart vapor retarders can reduce the risk of moisture damage in the building envelope by increasing the construction’s tolerance to moisture load, they are not suitable for every climate. Hot climates with high outdoor humidity are always under high RH conditions, which in turn, would cause

a smart vapor retarder to always be permeable and never provide the wall cavity with vapor retarding benefits. These materials also do not work well in buildings with exceptionally high, constant indoor humidity levels, such as indoor pools and spas. However, in rooms with short peaks of high humidity like restrooms and kitchens, the performance of the smart vapor retarder would not be affected because of the buffering action of interior finishes.

Conclusion

A holistic approach to building design is the best way to address moisture and air flow. As architects and builders affect one area like thermal performance, the flow of air and moisture are also impacted. Moisture in the wall is unavoidable, so it is important assemblies are designed with the potential to dry. By incorporating adaptable solutions like smart vapor retarders, occupant comfort can be managed and buildings set up for long-term structural success.

Ted Winslow is product manager, building science, systems, and technical marketing for CertainTeed Insulation. He serves the company as a technical resource on topics ranging from code reviews to sustainability programs and oversees development of CertainTeed insulation systems. Winslow holds a bachelor’s of science degree in mechanical engineering from Temple University. He can be reached at ted.winslow@saint-gobain.com.

- [Image]: http://www.constructionspecifier.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/airbarriers_membrain_SI_CertainTeed_5383.png

- [Image]: http://www.constructionspecifier.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/airbarriers_BlocksMoisture-ALT-v2-FA_text1.png

- [Image]: http://www.constructionspecifier.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/airbarriers_ReleasesMoisture-ALT-v2-FA_text1.png

- [Image]: http://www.constructionspecifier.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/airbarriers_Cti12PpkVapMb0001B.png

- [Image]: http://www.constructionspecifier.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/airbarriers_DOE_Map_only.png

- [Image]: http://www.constructionspecifier.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/Untitled-1.jpg

Source URL: https://www.constructionspecifier.com/using-vapor-retarders-to-manage-airflow-and-reduce-moisture/