Vision Reborn: Modern FRP composites restore ornamental masonry

by Guy Kenny and Steven H. Miller, CDT

Sometimes, the best way to restore an historic building is not the way it was originally built. The methods and materials of construction have changed, and newer options are available to re-create the original design. Labor-intensive approaches of a century ago are now prohibitively expensive. This

is especially true in the case of decorative details, which were sometimes hand-made. The range of available materials, by contrast, has expanded, offering the restoration architect more choices for achieving original appearance and function, and making it more durable and high-performing in the process.

Fiber-reinforced polymer composites (FRP) using glass fiber—commonly referred to as fiberglass—are increasingly being used to create large-scale architectural elements for restorations.1 FRP is extremely durable, does not corrode or rot, and bears the elements well. A single mold can be used multiple times in repetitive designs for economies of scale. One-off elements can often be created cost-effectively compared to alternative materials.

FRP holds detail sharply, and it can be colored and textured for a wide range of finishes. It is also lightweight—a massive, solid block of masonry can be replaced by an FRP shell a mere 6 mm (¼ in.) thick, reducing dead load and considerably simplifying installation. As FRP gains acceptance in construction, restoration is emerging as an area where it can be an effective solution for bringing faded grandeur back to flower.

Desecration of Detroit

Architectural restoration may be considered the act of re-fulfilling the original design intent. In many cases,

it is an implicit acknowledgment the architect’s ideas have outlasted the original materials, so it makes sense to preserve those ideas with new materials that are more durable, more appropriate, or both.

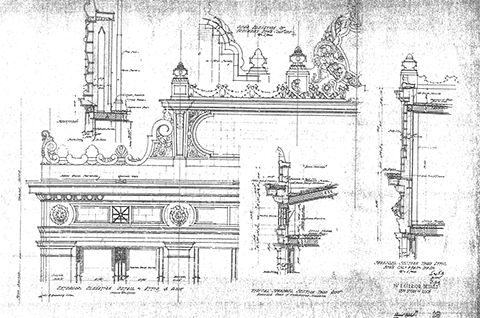

This is exactly the case with a series of restorations that have been happening in downtown Detroit, Michigan, where decorative masonry—long ago stripped from buildings—is being recreated in FRP. The old downtown is the site of many majestic late 19th and early 20th century buildings that once featured ornamental masonry, including large cornices crowning the classically inspired designs.

Then, in 1958, natural deterioration had its way with one such structure. A 6-m (20-ft) piece of cornice fell off the Ferguson Building, killing 80-year-old pedestrian Myrtle Taggart below. The mayor called for the elimination of “dangerous gingerbread,” and the city issued more than 1600 cornice violations. Rather than bring their cornices up to code, many owners simply stripped off the architectural crowns, leaving the edifices looking bare, their scars patched with (often mismatched) brick. Some went further, and ‘modernized’ the building exteriors, stripping almost all ornament. And thus it stayed for decades.

Now, following Detroit’s bankruptcy and the cratering of real estate values, many of these buildings have turned over ownership. The new owners are repurposing old commercial space into residential and mixed-use buildings, aided by tax credits for restoration of historical buildings. The grandeur of downtown Detroit is returning. In numerous instances, the masonry has been recreated with glass-fiber composite elements that look like the originals, but are a fraction of the weight of stone or terra cotta.

Rebirth of a grand edifice

The 19-story David Whitney Building is an illustrative case. Built in 1915, it occupies a prime location along Grand Circus Park at Woodward Avenue, in the heart of the city. With an august exterior, and a spectacular four-story sky-lit atrium at the center of its grand lobby, it quickly became a fashionable commercial address, tenanted by numerous medical practices. The building became well-known to generations of Detroiters who passed through its doors on the way to see the doctor.

It was ‘modernized’ in 1959, stripped of ornamental masonry and transformed into ‘mid-century modern.’ By the late 1990s, however, the building was vacant, and remained so for more than 15 years. The current owners began renovating the structure into a combination of hotel, high-end apartments, and retail in 2012. The remodel included restoration of the grand lobby, and re-creation of exterior ornamentation.