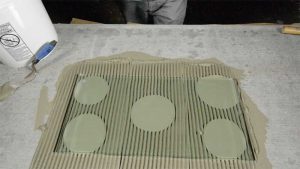

During installation, the tile installer will periodically lift random tiles after embedment to assess mortar coverage and distribution. If there are uncollapsed mortar ridges, or mortar voids on the substrate or on the back of tile, the installer could, for example, change to a larger-notched trowel to distribute more mortar. Unfortunately, the more typical corrective action is to randomly apply spots of mortar. Spot bonding adds more mortar to the substrate, but when the tile is once again embedded, the additional mortar does not evenly distribute across the substrate or on the tile’s underside.

If the tiles remain intact despite the poor surface preparation and marginal mortar coverage, there are other issues to address: excessive tile lippage, crooked grout joints, irregular grout joint widths, and inadequate slope for drainage. None of these issues are a simple fix and may require tear out to remediate.

Constructing a flat concrete floor

For larger concrete installations, a floor flatness (Ff) number is specified to indicate the required slab flatness. Ff numbers can range from 20 to 150, with higher values indicating a greater degree of flatness. A concrete slab for a commercial office space may only require an Ff of 30, whereas a concrete slab for a TV studio or narrow aisle warehouse requires a Ff number approaching 100. Unfortunately, a concrete slab constructed to a specified Ff number may not meet the sub-floor tolerance outlined in ANSI A108.02, at the time of the tile or stone flooring installation.

ASTM E1155, Standard Test Method for Degerming FF Floor Flatness and FL Floor Levelness Numbers, prescribes the measurement of Ff numbers within

72 hours of concrete placement. However, a floor that is measured or verified as flat at 72 hours does not remain flat. The residual moisture in concrete after placement will bleed to the concrete’s surface and evaporate if uninhibited by a curing membrane. As evaporation and slab drying occurs, the concrete slab shrinks and curls. The deformation is most pronounced at slab edges and construction joints. Consequently, the measured flatness within 72 hours will not be accurate after weeks and months of drying, particularly when the tile contractor is ready to start floor installation. Upon understanding concrete shrinks and curls after installation and does not remain flat, a design professional could attempt to solve the problem by simply specifying a higher Ff number than normally required for the project.

Ff number conundrum

As mentioned, ANSI A108.02 prescribes sub-floor surface variation for large-format tiles no greater than 3 mm in 3 m and no more than 1.6 mm in 0.6 m (1/16 in. in 2 ft), which is determined by measuring the gap between the substrate and a 3-m straight edge. There is no exact correlation between Ff numbers and straight edge measurements, but accepted industry correlations indicate a floor constructed to an Ff number of 50 approximately equates to a measurement of 3 mm in 3 m, and an Ff of 100 is around 1.6 mm in 0.6 m.

So, based on the approximate relationship between Ff numbers 50 and 100, and straight-edge measurements, one could assume there should not be any sub-floor flatness issues at the time of installation. While this is true theoretically, concrete drying shrinkage as previously described, will likely curl the slab out of spec for flatness even if Ff is high.

Another concern with specifying high Ff numbers is the concrete slab’s installation cost. The degree of floor flatness is a function of the finishing methods, tools, and precision employed by the concrete contractor. A hand-troweled concrete garage floor will not be as flat as one finished with a mechanical trowel. The former is cheaper to install. Consequently, achieving high Ff-numbered floors will be costly (Figure 2).

A better approach to substrate flatness

Achieving a substrate that remains flat until the time of tile installation is a challenge. Concrete drying shrinkage and the accompanying slab curl is almost a given. The money spent on initially achieving a high Ff number, high precision floor would be better spent on addressing floor flatness requirements through the installation of a self-leveling cementitious underlayment (SLU), at a lower cost and with a higher degree of flatness.

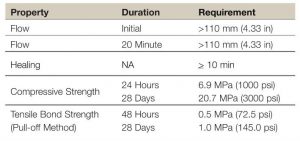

As a guide to SLU selection and specification, as well as product installation, two new ANSI standards are pending, with likely publication later this year:

- ANSI A118.16, Flowable Hydraulic Cement Underlayment/Self-leveling Underlayment; and

- ANSI A108.21, Interior Installation of Flowable Hydraulic Cement Underlayment/Self-leveling Underlayment, (Figure 3).