What the 2015 International Building Code means for wood construction: Part III

by Jacquie Clancy | April 17, 2015 10:00 am

by Buddy Showalter, PE

[1]

[1]To help translate what the latest changes to building codes mean for opportunities in wood construction, the American Wood Council (AWC) recently introduced four new standards that are adopted by reference in the 2015 International Building Code (IBC) and the 2015 International Residential Code (IRC).

Over the last two months, this author has covered updates to the 2015 National Design Specification (NDS) for Wood Construction[2] and 2015 Special Design Provisions for Wind and Seismic (SDPWS)[3]. These standards primarily govern engineering design and construction of wood structures to resist all applicable loads including high wind and seismic forces.

[4]

[4]This month, the 2015 edition of the ANSI/AWC Wood Frame Construction Manual (WFCM) for One- and Two-Family Dwellings will be explored to provide guidance for wood-frame construction in residential as well as commercial structures that fit within its scoping. The WFCM includes design and construction provisions for high wind, seismic, and snow loads for connections, wall systems, floor systems, and roof systems. A range of structural elements are covered, including sawn lumber, structural glued-laminated (glulam) timber, wood structural panel sheathing, I-joists, and trusses.

Primary changes reflected in the 2015 edition of the WFCM standard include:

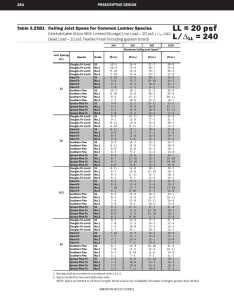

● updated design values for visual grades of Southern Pine reflected in tabulated spans for lumber framing members as referenced in the 2015 NDS Supplement: Design Values for Wood Construction;

● new tables to provide prescriptive wood-frame solutions for rafters and ceiling joists in response to new live load deflection limits for ceilings using flexible finishes (including gypsum wallboard) or brittle finishes (including plaster and stucco) as adopted in the 2015 IRC; and

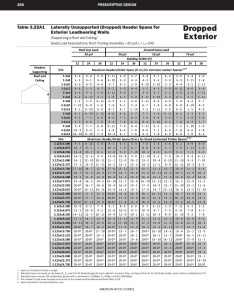

● revised header spans to reflect L/240 live load deflection limits for members supporting only a roof and ceiling as shown in 2015 IRC and IBC tables.

Tabulated engineered and prescriptive design provisions in WFCM chapters two and three, respectively, are based on the following loads from American Society of Civil Engineers (ASCE) 7-10, Minimum Design Loads for Buildings and Other Structures:

● 0 to 3.35 kPa (0 to 70) psf ground snow loads;

● 117 to 313 km/h (110 to 195 mph) 700-year return-period, three-second gust basic wind speeds; and

● seismic design categories A to D.

[5]

[5]

Tabulated spans for lumber framing members reflect changes to design values referenced in the 2015 NDS Supplement: Design Values for Wood Construction[6]. Notably, the 2015 NDS Supplement incorporates new design values for visually-graded Southern pine. The American Lumber Standard Committee (ALSC) Board of Review approved changes to these design values for all grades and sizes of visually graded Southern pine and mixed Southern pine lumber with a recommended effective date of June 1, 2013.

New tables for ceiling joist spans/capacities, rafter spans/capacities, and hip and valley beam capacity requirements have also been revised in the 2015 WFCM to clarify the live load deflection criteria and to associate live load deflection limits to cases with “no ceiling attached” and ceilings with “flexible finishes” and “brittle finishes.” Tables are added to address deflection criteria of L/LL=360 for brittle finishes (see example of Table 3.25B2). Flexible finishes are denoted as “(including gypsum board)” and brittle finishes are denoted as “(including plaster and stucco).”

Finally, roof header spans were revised in the 2015 WFCM to reflect L/240 live load deflection limits for members supporting only a roof and ceiling as shown in 2015 IRC and IBC tables. Tables are now based on L/240 instead of L/360 to be consistent with deflection limits for members supporting roofs and ceilings as shown in IRC Table R802.5.1 and IBC Table 2308.7.2 for rafters with ceilings attached to rafters, and IRC Table R802.4 and IBC Table 2308.7.2 for ceiling joists, respectively.

Importantly, new language in IBC 2309 allows for use of the WFCM for non-residential structures within its scoping limitations.

[7]

[7]As per IBC 2309.1, Wood Frame Construction Manual:

Structural design in accordance with the AWC WFCM shall be permitted for buildings assigned to Risk Category I or II subject to the limitations of Section 1.1.3 of the AWC WFCM and the load assumptions contained therein. Structural elements beyond these limitations shall be designed in accordance with accepted engineering practice.

Examples of non-residential applications include single-story wood structures or top stories in mixed-use structures in Risk Categories I or II.

Representing the predominant method of residential construction in the United States, history has demonstrated wood-framing to have inherent strength and durability. Today, increased industry and government focus being placed on ‘community resiliency,’ make design tools such as the Wood Frame Construction Manual become more relevant for construction.

The WFCM—available for download on the AWC website[8]—equips designers with engineered construction methods that result in buildings better able to withstand damage and protect occupants. Since the WFCM was first published in 1995, AWC has been providing a solution for design of wood-frame structures to resist natural disasters. Each successive edition of the standard continues to provide solutions to more severe events as required by building codes.

The fourth and final part of this series[9] will examine the 2015 Permanent Wood Foundation Design Specification (PWF), including structural requirements for designing wood foundations, most commonly used in the Upper Midwest. A permanent wood foundation system is intended for light-frame construction.

[10]John “Buddy” Showalter, PE, joined the American Wood Council (AWC) in 1992, and currently serves as vice president of technology transfer. His responsibilities at AWC include oversight of publications, website, helpdesk, education and other technical media. Showalter is also a member of the editorial boards for Wood Design Focus, published by the Forest Products Society, and STRUCTURE magazine, published jointly by National Council of Structural Engineers Associations (NCSEA), American Society of Civil Engineers/Structural Engineering Institute (ASCE/SEI), and Council of American Structural Engineers (CASE). Before joining AWC, Showalter was technical director of the Truss Plate Institute. He can be reached at bshowalter@awc.org[11].

[10]John “Buddy” Showalter, PE, joined the American Wood Council (AWC) in 1992, and currently serves as vice president of technology transfer. His responsibilities at AWC include oversight of publications, website, helpdesk, education and other technical media. Showalter is also a member of the editorial boards for Wood Design Focus, published by the Forest Products Society, and STRUCTURE magazine, published jointly by National Council of Structural Engineers Associations (NCSEA), American Society of Civil Engineers/Structural Engineering Institute (ASCE/SEI), and Council of American Structural Engineers (CASE). Before joining AWC, Showalter was technical director of the Truss Plate Institute. He can be reached at bshowalter@awc.org[11].

- [Image]: http://www.constructionspecifier.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/bigstock-Construction-Industry-1967697.jpg

- 2015 National Design Specification (NDS) for Wood Construction: http://www.constructionspecifier.com/what-the-2015-international-building-code-means-for-wood-construction-part-i/

- 2015 Special Design Provisions for Wind and Seismic (SDPWS): http://www.constructionspecifier.com/what-the-2015-international-building-code-means-for-wood-construction-part-ii/

- [Image]: http://www.constructionspecifier.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/AWC_WFCM-2015_112014_Page_001.jpg

- [Image]: http://www.constructionspecifier.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/AWC_WFCM-2015_112014_Page_292.jpg

- 2015 NDS Supplement: Design Values for Wood Construction: http://www.constructionspecifier.com/what-the-2015-international-building-code-means-for-wood-construction-part-i/

- [Image]: http://www.constructionspecifier.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/AWC_WFCM-2015_112014_Page_268.jpg

- AWC website: http://www.awc.org

- fourth and final part of this series: http://www.constructionspecifier.com/what-the-2015-international-building-code-means-for-wood-construction-part-iv/

- [Image]: http://www.constructionspecifier.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/Buddy-Showalter-Headshot.jpg

- bshowalter@awc.org: mailto:bshowalter@awc.org

Source URL: https://www.constructionspecifier.com/what-the-2015-international-building-code-means-for-wood-construction-part-iii/