Wildland Urban Interface (WUI): Specifying fire-resistant roofs

by tanya_martins | September 16, 2024 11:58 am

By Greg Keeler

[1]

[1]Considering fire activity over the last year, the consequences of wildfires can be seen across a wide range of geographies and climate zones. From the Canadian wildfires that spawned smog ingress across large swaths of the continental United States to the devastating destruction inflicted on the island of Maui, wildfires scathed regions across North America and around the globe.

Although wildfires are an expected seasonal threat in many regions—such as Canada and parts of the western United States—2023 was an exceptional year for wildfires. “Hot, dry, and windy conditions led to this unprecedented season,” says Jennifer Kamau, communications manager at the Canadian Interagency Forest Fire Centre (CIFFC). “There was significant fire activity in many parts of the country at the same time which doesn’t typically happen.”

Fire activity presents a particular concern when it occurs near the Wildland Urban Interface (WUI). The WUI is commonly described as the zone where structures and other human development meet and intermingle with undeveloped wildland or vegetative fuels. Population shifts toward the WUI following the onset of the global pandemic have led to more and denser construction in WUI areas. Compared to the previous 12 months, the number of U.S. households that moved into areas with a recent history of wildfire climbed 21 percent between March 2020 and February 2021.1

The heightened fire risk posed to structures built near the WUI applies to residential dwellings as well as light commercial buildings. Master planned communities (MPCs) are an example of construction projects that include a blend of residential and light construction such as community clubhouses, recreational centers, childcare facilities, apartments, and office complexes. While the International Building Code (IBC) does not have a specific designation for “light commercial construction,” this category of building is typically represented by one and two-story buildings used for Use Groups B, M, and R-2.

In addition to the threat posed by combustible vegetation and debris in the WUI, technology also presents issues when it comes to fire safety on roof assemblies. For example, as efforts to reduce the environmental footprint of buildings continue, some cities require solar-ready or solar power components in new construction.

Increased building near the WUI and growing interest in solar assemblies are two factors influencing building code officials to increasingly call for fire-resistant products. The roof presents a special consideration for helping protect exterior fire resistance given the potential for fire-blown vegetation and debris to land on the roof.

How roof assemblies are classified for fire resistance

When it comes to fire resistance, it is important to note that roofs are tested and classified as assemblies. Considering residential and light commercial buildings, the roof assembly is evaluated according to its ability to resist fire from the outside of the building.

Take a look at three classifications for roofs based on their demonstrated performance to resist fire during testing. The three classifications described in ASTM E108-20a, Standard Test Methods for Fire Tests of Roof Coverings, are described as follows:

[2]

[2] [3]

[3]- Class A tests are applicable to roof coverings that are expected to be effective against severe fire exposure, afford a high degree of fire protection to the roof deck, do not slip from position, and are not expected to present a flying brand hazard.

- Class B tests are applicable to roof coverings that are expected to be effective against moderate fire exposure, afford a moderate degree of fire protection to the roof deck, do not slip from position, and are not expected to present a flying brand hazard.

- Class C tests are applicable to roof coverings that are effective against light exposure, afford a light degree of fire protection to the roof deck, do not slip from position, and are not expected to present a flying brand hazard.

Code-required testing required for roof assembly classifications

Two code required tests are used to classify roof assemblies installed on residential and light commercial structures: ASTM E108, Standard Test Methods for Fire Tests of Roof Coverings, and UL 790, Fire Tests of Roof Coverings. Both tests measure an assembly’s ability to slow or impede a fire from the exterior to the underside of a roof deck under the conditions of exposure. Impeding an exterior fire’s progress can allow more time for occupants to egress a building.

Regardless of the roof covering, the testing process is the same. The test methods cover all of the components in the assembly, including the roof covering materials (shingle, tile, metal, etc.), the underlayment, and the sheathing. While the test methods do not necessarily replicate the expected performance of roof coverings under all fire scenarios, they serve as a basis for comparing roof coverings when subjected to fire sources.

Of course, wind is a fierce factor in propagating fire spread. Each of the tests evaluate how a burning brand affects the assembly as it is exposed to an airflow. The simulated exposure tests evaluate if the roof covering material will develop flying burning material (flying brands) or result in a sustained flame on the underside of the deck when subjected to a 19 km (12 miles) per hour (5.3-m/s) wind.

If there is a path of air in the assembly because the shingles or other roof coverings have buckled, it will be more difficult for an assembly to pass the test. The specific covering will determine the point of vulnerability targeted in testing. The most vulnerable part of the deck is where the brand is located. With asphalt shingles, the most acute point of vulnerability is typically the horizontal joint in the roof deck. The brittle nature of concrete clay tile coverings means the material can break anywhere and allow for the brand to fall through the resulting openings.

The ability of the underlayment material to take on the heat from a fire is critical in metal roofs as metal rapidly conducts heat into the underlying materials.

While ASTM E108 and UL 790 are comprised of three separate tests (burning brand, intermittent flame, and spread of flame), the most stringent test for most steep-slope roof coverings is the burning brand test.

- The Class A test incorporates a brand that measures 0.3 x 0.3 m (1 x 1 ft) by 57.15 mm (2.25 in.) tall and is comprised of hardwood pieces with air spaces in between. The brand is placed in the most vulnerable area of the deck.

- The Class B testing uses two brands half the size of the brands in Class A testing.

- The Class C test is much smaller and uses 20 tiny brands placed on the roof covering. This test is not stringent in any respect.

The duration of the test is 1.5 hours but can be shorter, say 45 to 50 minutes, based on the performance observed. Roof material coverings are installed in such a way that the fewest number of layers in the system are over the top of the joint where air can pass through.

What criteria must be met to earn a “pass” on the test? Generally, if there are no indicators of fire activity on the top surface or underside of the deck and the temperature is in the 121 to 149 C (250 F to 300 F) range, and if no glowing brands are coming off of the deck, an assembly is considered to pass the test. In such situations, an assembly may pass testing before the 1.5-hour test period has elapsed. By the same means, if the deck is still glowing red hot and none of the aforementioned activity is present after 1.5 hours has elapsed, an assembly is considered to have passed the test. In order to obtain the desired classification, four consecutive decks must pass the burning brand test. At no point in the test is the roof assessed for watertightness, except for wood shakes and shingles.

Designing Class A assemblies: Considering roofing underlayment

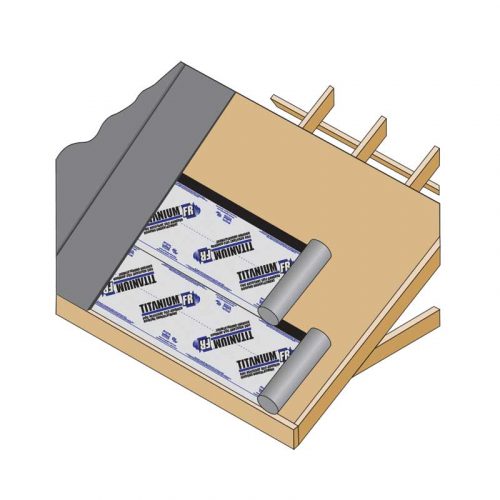

Installed between the shingles and roof sheathing, roofing underlayment does much more than keep water from infiltrating into the home. The choice of underlayment can play a crucial role when it comes to supporting safety—from creating a walkable surface for workers, to supporting a roofing assembly’s fire resistance. In recent years, there has been a strong focus on moving away from traditional felt underlayment to synthetic underlayment materials that are tough and effective at repelling water compared to felt. Innovation continues with new options for fire-resistant underlayment that can meet Class A testing requirements.

In 2023, a manufacturer introduced a self-adhered underlayment which can be installed under asphalt and metal assemblies as well as in solar assemblies. The formulation includes a proprietary blend of fire-resistant technologies including retardant compound and facer. Beyond being fire-resistant, the underlayment also supports worker safety on the rooftop with enhanced walkability and slip-resistance. The product can handle up to 180 days of UV exposure.

Looking forward: Finding a common language

[4]

[4]Simply introducing fire-resistant products into the marketplace is not enough. The vocabulary of different classifications must be understood as well. In speaking with firefighting groups, code officials and stakeholders across all jurisdictions, it is apparent the industry suffers from inconsistency in the language used to address fire resistance. There is a lot of debate at the international code level regarding the semantics of fire resistance, classifications and listings, and industry stakeholders are working to make the language more consistent.

The severity, size of fires, and resulting financial losses experienced in recent years point to a heightened risk for all parties—from product specifiers to construction teams to the occupants of residential and light commercial structures. Additionally, more installations of solar panels are adding highly flammable components to roofs. Specifying materials in the roofing assembly that can stand up to harsh conditions as reflected by Class A roofing assemblies measured per ASTM E108 or UL 790 can support specifiers in recommending products for traditional steep slope and energy-generating roof assemblies.

Notes

1 Read the article on Bloomberg at www.bloomberg.com/graphics/2021-moves-into-fire-zones/.

Test your knowledge! Take our quiz on this article[5].

Author

[6]

[6]

Greg Keeler is the technical services leader for Owens Corning (OC). He is primarily responsible for providing worldwide codes and standards expertise to the OC roofing and asphalt business. Keeler is also highly regarded in the roofing industry as an expert on all code requirements for roofing products. He is actively involved in the International Code Council (ICC), Florida, and other state code modification processes.

- [Image]: https://www.constructionspecifier.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/Wildfire.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.constructionspecifier.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/Underlayment.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.constructionspecifier.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/RoofInstallation-Diagram.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.constructionspecifier.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/Titanium-FR_diagram.jpg

- Take our quiz on this article: https://www.constructionspecifier.com/fire-resistant-roofs-quiz/

- [Image]: https://www.constructionspecifier.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/Greg-Keeler.jpg

Source URL: https://www.constructionspecifier.com/wildland-urban-interface-wui-specifying-fire-resistant-roofs/