Wood construction and the International Building Code

by Catherine Howlett | January 1, 2013 4:18 pm

[1]

[1]

Photo © W.I. Bell. Photo courtesy WoodWorks

by Kenneth Bland, PE, and Paul Coats, PE

In building code history, wood structures have been highly regulated. Experience gained from past fires contributed to what is still the basis of today’s modern building codes, which are traditionally slow to change, and therefore, retain limits and restrictions established in response to what occurred centuries ago.

Today’s building codes may lack flexibility in materials and methods often justified on a case-by-case basis through code variances or establishing equivalencies. While wood has always been a material of choice for residential construction, options in the code for a certain class of commercial structures remain few—primarily steel and concrete. However, this is changing, and new developments in technology and updates to the International Building Code (IBC) are making it possible.

The 2012 IBC regulates allowable building height and floor area based on structural framing materials, either combustible or non-combustible, and fire-resistance ratings of walls, floors, and roof structures. With increasing recognition in IBC for fire sprinklers and other fire safety building features, the possible size and types of wood buildings has dramatically increased. The IBC permits one- and two-story business and mercantile buildings of wood construction to be unlimited if they have a reasonable separation distance from other buildings and a fire sprinkler system. Residential multi-family buildings can be taller than in the past—up to 30 m (85 ft) in some cases—and wood features in otherwise non-combustible buildings are more readily permitted. This is all timely for both ever-expanding environmental considerations and new developments in wood technology.

An alternative approach

National Fire Protection Association (NFPA), 5000, Building Construction and Safety Code, has a similar approach. However, it contains an alternative to regulating building height and area that emphasizes the number and frequency of specific fire-resistive elements, such as fire barriers rather than building size, in regard to fire risk. This idea has been codified in Appendix D of NFPA 5000—an approach that uses fire-resistance rated separations to compartmentalize buildings regardless of size. In other words, building size is not limited according to construction type, but rather a maximum area between fire-resistance rated elements in the building is established.

[2]

[2]Data courtesy International Building Code (IBC)/American Wood Council (AWC)

This idea has not yet been successful in the IBC, which still relies on traditional height and area limits by means of a table with standard ‘per story’ area limits. However, this could change in the future.

Basic areas and increases in the IBC

IBC recognizes two overarching types of construction: non-combustible and combustible. These are reflected in the construction type categories of the IBC. Types I and II are non-combustible, while Types III, IV, and V are combustible. IBC, Table 503 establishes building area and height limits in accordance with the construction type of the building. However, the tabular allowable areas are only a starting point for how the code regulates building area based on construction type. The presence of features such as fire sprinkler systems, separation from property lines, and fire-resistance ratings permit buildings much larger than the tabular areas.

Fire sprinklers and open frontage—the separation of the building from property lines and other structures—are the most important features for larger building areas. Sprinklering a building will yield a minimum 200 percent increase in tabular allowable area per story for most low-rise buildings, and 300 percent for single-story buildings. Fire separation of 9.1 m (30 ft) will yield an additional 75 percent. The increases are cumulative; with some additional separation, the code removes all area limits for many use groups in single and two-story buildings—they become what IBC calls “unlimited area buildings” (Section 507) .

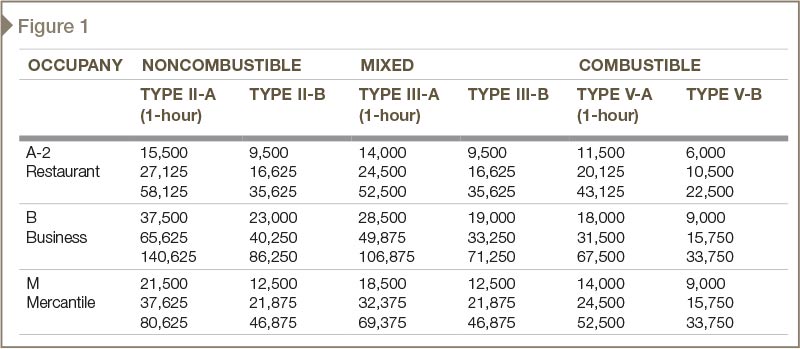

The table in Figure 1 shows a comparison of allowable building size for common types of construction and commercial use groups in low-rise buildings. Construction Types III and V are primarily combustible (e.g. wood), and Types I and II are non-combustible (e.g. steel or concrete). The numbers in each cell (from top to bottom) indicate the basic tabular area per story, the maximum increase for open frontage (i.e. distance from property lines), and the combination of full-open frontage and sprinklers. The numbers for Type III-B (combustible, unrated except for exterior walls) and V-A (combustible, one-hour rated) are both roughly equivalent to those for II-B (non-combustible and unrated).

[3]

[3]Data courtesy International Building Code (IBC)/American Wood Council (AWC)

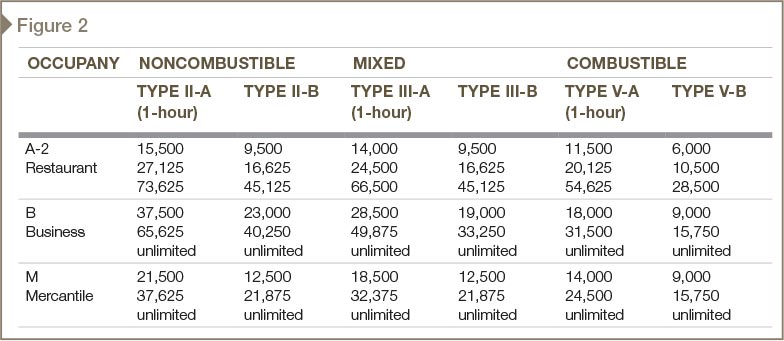

Looking at a similar table for single-story buildings (Figure 2), the unlimited category makes size distinctions even less.

Benefits of sprinkler trade-offs

Over the last 20 years, IBC has changed to recognize safety benefits provided by automatic fire sprinklers. Many buildings are required to be sprinklered because of a combination of floor area and use (i.e. occupancy group). Since sprinklers may be required regardless of construction type, designers should consider the most economical materials permitted by the code given the sprinkler mandate. Permitted area increases due to sprinklers should be considered when selecting the type of construction early in the design process, since sprinklers may be required by other provisions of the code.

[4]

[4]Photo courtesy APA–The Engineered Wood Association

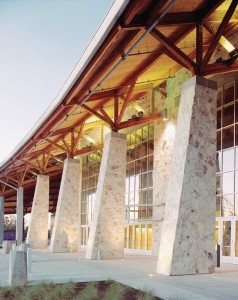

Roof structures are one of the primary exceptions noted in the IBC allowing significant use of wood in many commercial buildings. Projects where the roofing structure is a defining feature of the building—as seen here in the Skagit Multi-Modal Transportation Center in Mount Vernon, Washington—often take advantage of this permission. Photo courtesy APA–The Engineered Wood Association

Sprinklering a building, regardless if it is required by use group floor area, can also reduce costs elsewhere in the code. The 2012 IBC has at least 20 significant ‘trade-offs’ (or, ‘trade-ups’ for what may be considered better fire protection than passive systems). These include:

- reductions in both corridor wall ratings and opening protection;

- relief from areas providing areas of refuge in exits;

- increased exit travel distances;

- reductions or elimination of certain fire-resistance-rated separations;

- lowered requirements for fire and smoke dampers; and

- decreased restriction on interior finishes.

A sprinkler system can often pay for itself by eliminating features that may otherwise be required in the building, while also opening the door for wood construction at the same time by increasing the allowable building height and area.

Due to the fire protection afforded by active suppression systems, increases in building area and size are set forth for all construction types in IBC, Chapter 5, when sprinklers are installed.

The use of sprinklers does not eliminate all passive fire protection features required by IBC. The possibility of sprinkler failure due to human error (e.g. closed valves), or other reasons, necessitates an established level of passive protection that remains in the building code. A reasonable balance between active and passive fire protection is routinely a topic of debate in the code development process.

Type III construction and wood

By definition, Type III construction in the IBC requires non-combustible exterior walls (e.g. steel or concrete). However, there is an exception for the substitution of fire-retardant treated wood walls in exterior walls. Therefore, a Type III building can be comprised entirely of wood and still meet the construction type’s minimum requirements. This allows even greater areas and heights, as shown in Figure 1 and 2 (page 51 and 52).

Fire resistance-rate construction

The type of construction is categorized as non-combustible or combustible and further subdivided based on fire-resistance rating of building elements. The combustibility of a product is measured by ASTM E136, Standard Test Method for Behavior of Materials in a Vertical Tube Furnace at 750 C (1382 F), which measures mass and volume loss when exposed to fire. While this test demonstrates whether the material will burn, it does not consider how the product reacts to a sustained fire when supporting loads.

To determine how a structural element or assembly will react under fire exposure, ASTM E119, Standard Test Methods for Fire Tests of Building Construction and Materials, or Underwriters Laboratories (UL) 263, Fire Tests of Building Construction and Materials, are used. Fire-resistance testing provides results based on the duration the element or assembly maintained its structural integrity. This performance-based approach begins to breakdown the traditional approach to regulating a product based on its combustibility and focuses on its ability to perform the necessary function.

Fire resistance of assemblies is typically achieved through the use of gypsum board or spray fire-proofing to protect beams and columns from fire exposure. Fire-rated wood assemblies also rely on gypsum wallboard, but solid or engineered wood elements can be sized to achieve a specified fire-resistance rating. As wood elements burn, the char becomes an insulator preserving the strength of inner fibers. Calculations require the members to be designed in accordance with approved methods for calculating the fire resistance of exposed wood members. The method called out in Chapter 7 of IBC uses Chapter 16 of the National Design Specification for Wood Construction (NDS) published by the American Wood Council (AWC). AWC’s Technical Report No. 10, “Calculating the Fire Resistance of Exposed Wood Members,” gives examples of calculations.

Primary exceptions

Apart from the increased height and area due to sprinkler systems and open frontage, two primary exceptions allowing significant use of wood in many commercial buildings are for roof structures and pedestal buildings. By virtue of a footnote in the construction type table, most roof structures may be wood even in non-combustible construction types. Structures where the roof itself is a defining feature of the building often take advantage of this permission.

[5]

[5]Photo courtesy APA–Engineered Wood Association

IBC Section 510 describes some structure where a combustible building may be built on a non-combustible “pedestal” (typically lower stories for a parking garage). Buildings of this type may exceed the regular story limits, by virtue of having Type I construction on the bottom part and a fire-resistive separation between the upper building and the lower one. Early restrictions on the use of the first level were lifted from the 2012 IBC. Further changes in the latest code cycle are providing increasing flexibility in relative heights of lower and upper structure, allowing wood ‘tops’ to what normally may have to be non-combustible buildings.

Except for exit enclosures, most interior finishes can be exposed wood, especially if the building is sprinklered. IBC’s Chapter 8 indicates the required flame spread, and different species of wood have different flame spreads. (Wood species and the various flame spreads are listed in the AWC publication, Design for Code Acceptance No. 1[6]—Flame Spread Performance of Wood Products.) Sprinklers automatically reduce the required flame spread classification by one classification in most cases.

Cross-laminated timber

Cross-laminated timber (CLT) is a newer technology that essentially makes whole wall and floor sections from multiple layers of dimensional lumber laminated together in cross-wise fashion—similar to plywood but in dimensions equal to typical heavy timber or frame wall and floor sections.

CLT is currently permitted as elements of Type III and Type V construction, and will be recognized by the 2015 IBC as Type IV construction. Until the codes catch-up to this evolving technology, CLT can currently be accepted under the alternate materials and methods sections of the code.

With this development, much of the self-limiting, load carrying capacities of heavy timber are eliminated, allowing wood buildings to be unlimited in height, from a structural standpoint. The environmental benefits, both global and local to the building, make this new alternative for buildings that up to now have been the domain of steel and concrete.

Conclusion

Cost consideration, environmental concerns, and evolving aesthetic taste continue to bring wood to the forefront in design. The International Building Code is increasing in versatility and designers can and should take note of it. The current code system of limiting building size based on materials may soon be obsolete. The benefits for sprinklers, the unlimited area provisions, and the calculated fire resistance provisions of the IBC have dramatically reduced the road-blocks to innovative wood structures.

Kenneth Bland, PE, is the vice-president of code and regulations for the American Wood Council (AWC). He served as building official of Keene, New Hampshire prior to joining AWC in 1988. Bland can be contacted by e-mail at kbland@awc.org[7].

Paul Coats, PE, is a regional direction for AWC and has also worked for BOCA International, a predecessor organization to the International Code Council (ICC). He can be contacted at pcoats@awc.org[8].

- [Image]: http://www.constructionspecifier.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/wood_Image-3_High-Res.jpg

- [Image]: http://www.constructionspecifier.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/01/wood_fig1.jpg

- [Image]: http://www.constructionspecifier.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/01/wood_fig2.jpg

- [Image]: http://www.constructionspecifier.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/01/Image-4_Skagit-Roof.jpg

- [Image]: http://www.constructionspecifier.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/01/wood_Image-7.jpg

- Design for Code Acceptance No. 1: http://www.awc.org

- kbland@awc.org: mailto:kbland@awc.org

- pcoats@awc.org: mailto:pcoats@awc.org

Source URL: https://www.constructionspecifier.com/wood-construction-and-the-international-building-code/